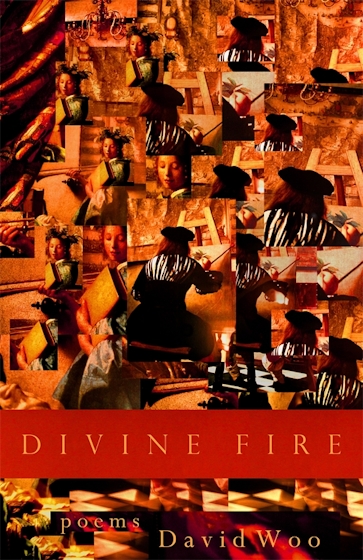

Divine Fire

Poems

Title Details

Pages: 104

Trim size: 5.500in x 8.500in

Formats

Paperback

Pub Date: 03/01/2021

ISBN: 9-780-8203-5884-0

List Price: $20.95

eBook

Pub Date: 03/01/2021

ISBN: 9-780-8203-5885-7

List Price: $20.95

Series

Divine Fire

Poems

An astonishing vision of the world right now that searches for meaning through the exploration of timeless themes, both sacred and profane

Skip to

- Description

- Reviews

How to find wisdom and spiritual sustenance in a time of crisis and uncertainty? In Divine Fire, David Woo answers with poems that move from private life into a wider world of catastrophe and renewal. The collection opens in the most personal space, a bedroom, where the chaotic intrusions of adulthood revive the bafflements of childhood. The perspective soon widens from the intimacies of love to issues of national and global import, such as race and class inequality, and then to an unspoken cataclysm that is, by turns, a spiritual apocalypse and a crisis that could be in the news today, like climate change or the pandemic. In the last part of the book, the search for ever-vaster scales of meaning, both sacred and profane, finds the poet trying on different personas and sensibilities—comic, ironic, earnest, literary, self-mythologizing— before reaching a luminous détente with the fearful and the sublime. The divine fire of lovers fading in memory—“shades of the men in my blood”—becomes the divine fire of a larger spiritual reckoning. In his new book of poems, Woo provides an astonishing vision of the world right now through his exploration of timeless themes of love, solitude, art, the body, and death.

I expect David Woo to be one of the two or three poets of his generation. Divine Fire is even more wise, eloquent, and light-bringing than was The Eclipses. David Woo now writes the poems of our climate, in the tradition of Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, and Elizabeth Bishop.

—Harold Bloom, author of The Daemon Knows

The grace with which David Woo’s poems transform knowledge, as in insight and learning, into form and feeling and then back again into transformed knowledge is just astonishing.

—Vijay Seshadri, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of 3 Sections

Divine Fire is even better than The Eclipses, praising which I pretty much used up my store of superlatives. It’s funnier, sexier, wiser, more grief-stricken, more profoundly literary, more personal without ever once stooping to mere revelation. It makes me think of that remark of Mallarmé’s about all earthly existence belonging in a book—or, as tweaked by Merrill in 'The Book of Ephraim,' ‘the world was made to end (pour aboutir)/ in a slim volume.’ In fact, a very apt comparison can be made with ‘Ephraim,’ despite their obvious differences: it feels more and more, with each rereading, like an entire life, ‘a sea to swim in,’ one I sense I will never quite get to the bottom of, or want to.

—Daniel Hall, author of Under Sleep

David Woo’s quietly magisterial, wide-rangingly, allusive second book of poems, Divine Fire, stations us like the man Kafka imagined in front of a mirror containing all of the world’s wisdom, but unlike that man who 'desired . . . to ensure . . . the silvering' properties of the mirror would last—a kind of fool’s errand—Woo shows us a way through the chimera of the world’s wisdom to a 'real life . . . mirror . . . nailed to the ceiling' of 'some red-velvet motel,' beneath which we move achingly aware of 'all those limbs' before us, with us, that have knotted and unknotted in the 'art of becoming another.' What we see in the 'real life' mirror is not world wisdom but a divine fire that both makes and destroys us so that 'what remains is something wee/ wee and oh-so-sempiternal, the self/ unselfing another, world without end.'

—Michael Collier, author of My Bishop and Other Poems

I’ve now read Woo’s new collection, Divine Fire, three times, and each time I find it more remarkable. His poems—wry even in the face of racism, death, and the apocalypse—never fail to disturb my assumptions.

—Ron Charles, Washington Post